Evan Wright – American author

Military failure is everywhere. As managers and leaders, we can learn from classic instances of so-called military incompetence. There are many examples from the disastrous Allied landing at Gallipoli in World War I, to operation Barbarossa, the failed Nazi invasion of Soviet Union in World War II and to the 1954 Battle of Dien Bien Phu in French Indochina which resulted in catastrophic defeat for the French.

However, few examples could be more humorous, without loss of human life and just as instructive for managers on ‘what not to do’ as the Great Emu War of 1932.

What are the characteristics of an emu?

They are an enormous bird second in size to the African ostrich. They cannot fly and have an average height of over 2 metres, very strong legs, can run up to 50 kph, and naturally flock in large numbers.

Background to ‘the conflict’

Following the end of World War I, the Australian government ‘rewarded’ returning soldiers with farm land. In Western Australia the veterans or ‘soldier settlers’ were allocated farmland which was very marginal for the growing wheat. Very few were experienced in agriculture. To add to the farmers’ challenges a severe drought hit, and 20,000 starving emus came in from the desert and commenced in destroying the existing wheat crop. Furthermore, this occurred in the Great Depression with a background of rising unemployment and falling wheat prices

The veterans lobbied their local parliamentary representatives to provide assist to rid the country of the emu ‘menace’. A Western Australian Senator, Sir George Pearce, recommended that the veterans and troops should tackle the problem head-on and hunt the birds. The government needed to show support for the famers. As the saying goes, “never waste a good crisis”.

What better opportunity for politicians than to provide a well-publicised effort to protect the former veterans who were ‘doing it tough’ and call in the army?

So certain that the operation would be a success, a cinematographer was hired from Fox Movietone to cover the hunt.

On the first day of ‘war’ less than 50 birds were killed out of the thousands shot at. The biggest misconception about the Emu War is that it was a massive assault staged by the Australian military. It was just three soldiers, a small truck, two Lewis machine guns, and 10,000 rounds of ammunition. A machine gun was mounted on the truck, but the truck could only travel a 30 kph over rough land, no match for an emu who could run at 50 kph and the truck could only chase one emu at a time. Furthermore, the soldiers couldn’t stabilise a machine gun on the vehicle or shoot with any accuracy.

The Great Emu war lasted less than six weeks – 986 emus were killed, and 9,860 rounds of ammunition was expended. Ten rounds per dead emu – not a great kill ratio although the only loss for the soldiers was their pride!

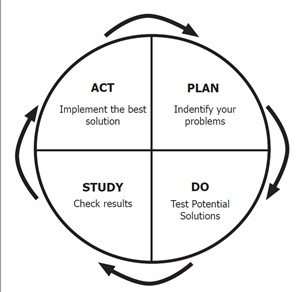

A more effective plan was later introduced. Rather than use brute-force the government set aside money for bounties. The farmers did the hard work of tracking and shooting the emu menace. Two years later in 1934, nearly 58,000 bounties were claimed.

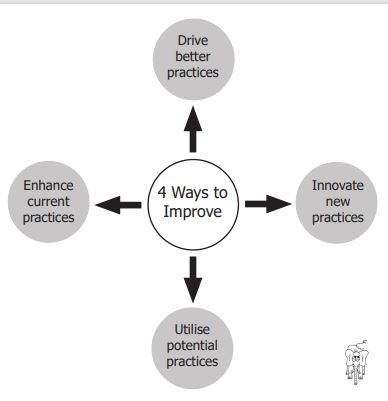

What lessons are there for us as managers in the ‘great emu war’?

Here are three worth considering.

- Be aware that politicians do not have the answers for problems of business. Many, in particular politicians today have no business or managerial experience. Governments overpromise and under deliver. The management of the COVID pandemic is a good example.

- Technology is not the answer. Technology is an enabler and not the magic bullet to solve the problem. Having a motor vehicle and machine guns did not solve the problem as it was not clearly defined.

- The most successful solutions involve the parties directly involved in the problem. By offering bounties, the farmers had a direct incentive to make it work – and they made money out of the bounties and reduced the number of emus attacking their crops.

#thenetworkofconsultingprofessionals