“Any fact is better established by two or three good testimonies than a thousand arguments”.

Nathanial Emmons – influential American theologian

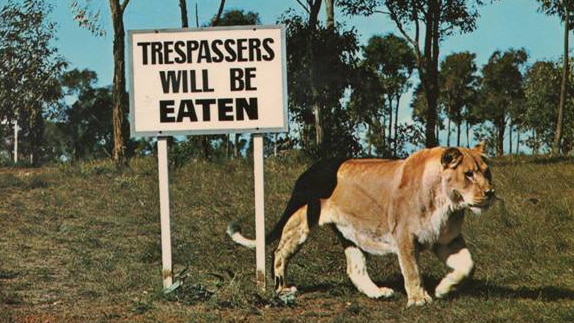

Before the opening of open range zoos in Australia, there was an African Lion Park located on the edge of suburban Sydney. It was owned and managed by the famous Bullen circus family. Families could drive through the park and get close to lions. As a kid I can remember visiting and reading the signs warning you that if you got out of your car you could be eaten!

How exciting a visit was for young children! As a visitor you had the chance to see lions rubbing up against your car and even licking the windows!

Interestingly, the park also provided a disposal service for the local community for their unwanted livestock. Classified advertisements ran in the local newspapers for the removal of sick or injured sheep, cows and horses. The park closed in 1991 but the lions remained!!!

Now, Australia is renowned for its dangerous creatures from the sharks, spiders, jelly fish, snakes to crocodiles. In 1995, the inhabitants in the townships of Warragamba and Silverdale close to the lion park were reportedly ‘terrorised’ by lions. In Australia, surely this was an urban myth!

Well, facts can be stranger than fiction.

So, what happened and was it true or just an urban myth?

Yes, three lions escaped. The local police received a call from a startled motorist who saw a lion cross the road and they had to attend to a “lion wandering the streets”. Two of the lions were recaptured and returned to the park. However, one lion continued to wander the streets and after killing a dog was shot and killed by the park’s owner in a suburban street.

How did the lions escape?

Even though the park was closed, lions could still be heard roaring and been seen being fed from the boundary fence. Living next to a defunct lion park were two 12-year-old boys. Now boys will be boys. One day on the park’s boundary fence, they kicked in a rusted grate on a stormwater culvert and wandered in. They did some exploring, fished for yabbies and then headed back home back through the culvert and broken grate. The thought of lions escaping was apparently furthest from their minds, and alas that occurred.

So, this was not an urban myth!

Is there a lesson about urban myths here for us as managers?

Years ago, a colleague related the story of a business owner who re-employed a person to run the business who had sacked the week before for non-performance. Sometimes facts can be stranger than fiction even if they sound like an urban myth or an episode of Utopia the ABC TV series that parodies how bureaucracies work. A great example is the Harold Holt Memorial Pool in Melbourne. The local Council named the pool after Prime Minister Harold Holt, who drowned while swimming in the surf near Melbourne and whose body has never been found!

When it comes to your own corporate myths, I am not suggesting that you make up stories. Instead, make an effort to find and share them. These stories can be a vehicle to connect and engage with current employees and customers. Without the ongoing sharing of the story, the actual event will be lost or forgotten, and companies will start to lose their corporate memory.

For example, in 1998 there was the shopping trolley story involving Roger Corbett, the then CEO of Woolworths Australia a supermarket company. Apparently, he came across an empty Woolies trolley and then pushed it all the way from Sydney’s Circular Quay near the Opera House to the Town Hall supermarket. At the time, Corbett was creating a culture of attention to detail and cost reduction. Although he retired in 2006, the story is still shared today. It has become an urban myth in the company.

Another business urban myth is the story set in 1960s about Sir Frank Packer, millionaire media owner and father of media baron Kerry Packer. The story goes that Sir Frank, a pugnacious, autocratic and often difficult businessman found himself in an elevator of his Sydney office building with a shabbily dressed man, and was outraged. Packer tells the man he’s a disgrace to his firm, fires him, and hands him $1,000 to buy a new suit. The ‘fired’ man just grins — he was a freelance photographer who stopped by to visit a friend who worked in the building. The story apparently circulated when Sir Frank believed his employees were not meeting his dress standards.

Does your organisation have stories that could be used to enhance and build a positive and constructive culture?

It could be worth exploring.

#thenetworkofconsultingprofessionals