“To function efficiently, any group of people or employees must have faith in their leader”

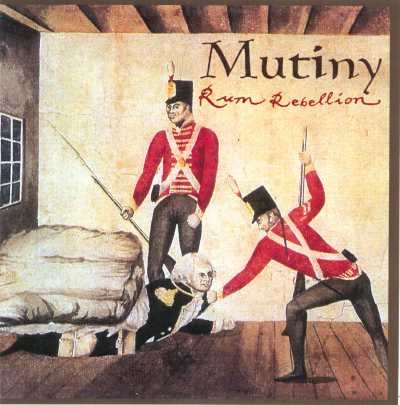

– William Bligh: of mutiny on the Bounty fame

The above quote is rather ironical, considering Bligh was the subject of the most famous historical maritime mutiny, the Mutiny on the Bounty. It was made famous or infamous in three films in 1935, 1962 and 1984. None of these films were sympathetic to Lieutenant William Bligh, the officer in charge (note that he was not a Captain). Interestingly, Bligh was also the subject of another less well-known mutiny, when as Governor of NSW he was overthrown in a military coup in what was known as the Rum Rebellion.

Bligh’s mission was to transport breadfruit plants from Tahiti to feed slaves on plantations in the West Indies. A little known and important fact was that the Bounty had no marines onboard. During this period, it was customary to have marines onboard a naval vessel to ensure discipline and to separate the ordinary sailors from the officers as well as to protect the crew from hostile natives. The Bounty had been converted into a ‘floating greenhouse’ to house the breadfruit so there was no room for a party of marines. Bligh, as only a Lieutenant rather than a Captain, had to rely on his ability to control the sailors onboard. Also, there were no other officers onboard the Bounty.

Bligh was a very experienced sailor, coming from a family with a long naval tradition. He went to sea as a cabin boy at the age of seven and travelled with Captain Cook as the chief navigator on Cook’s third and final voyage. His navigation skills would become extremely useful in the future. Historical reports state that Bligh was a strict disciplinarian and was given to outburst of ‘towering rage’ and ‘bad temper’, which obviously did not endear him to the crew. Strict discipline was, however, not unusual for the times.

Setting sail in 1787, the Bounty was to travel to Tahiti around Cape Horn. However, after terrible storms and weather experienced trying to round Cape Horn, Bligh was forced to sail to the pacific ‘the long way’, across the Atlantic, around the Cape of Good Hope, into the Indian Ocean, through the Great Southern Ocean under Australia and into the Pacific. After this unscheduled extended voyage, the Bounty arrived in Tahiti. Here it stayed for five months to allow the breadfruit trees to mature to be able to be transported. During the stay many of the crew were mostly idle and formed romantic relationships with the local women whilst enjoying the tropic climate of this Pacific paradise.

The Bounty left for the West Indies in April 1789. Later in the same month, the crew led by Fletcher Christian mutinied. Bligh and 18 loyalists were cast adrift in 7m open boat. Considering the circumstances, with their holiday cut short, it is perhaps not surprising that the crew mutinied!

Following the mutiny, the Bounty returned with the mutineers to Tahiti. Meanwhile, the boat with the 18 loyalists was so overloaded, it required constant bailing to remain afloat. Over the next 47 days and over 6,700 kms, Bligh and crew sailed to Timor in the Dutch East Indies. Bligh, ever the disciplinarian ensured severe rationing of food and water – 28g of water and 40g of biscuits per crew member per day. Despite exposure, malnutrition and dehydration the boat arrived without any loss of life, apart from a crew member killed by natives in Tonga. The success of the journey is testament to Bligh’s navigational skills, sheer will power, determination and disciplined leadership.

What do you think are lessons for leaders from the mutiny on the Bounty?

Here are three.

- Leadership and Team Dynamics: The Mutiny on the Bounty underscores the critical role of leadership and its impact on team dynamics. Managers should prioritise fostering positive leadership qualities, such as fairness, respect, and effective communication, to create a harmonious and productive work environment.

2. Addressing Employee Dissatisfaction: Understanding and addressing employee dissatisfaction is essential. In Bligh’s case, his tyrannical leadership contributed to the mutiny. Managers should encourage open channels of communication and actively seek feedback to prevent grievances from festering.

3. Crisis Management and Adaptability: Bligh’s remarkable journey in the open boat highlights the importance of crisis management and adaptability. Managers should equip themselves with the skills and resilience needed to navigate unexpected challenges, providing stability and direction during crises.

Can you think of any others?

How do you think Bligh should be remembered?

Bligh’s reputation was a mixture of admiration for his survival and navigational skills, and criticism for his leadership approach. He is remembered as a figure of resilience, skilled navigation, and unwavering dedication to his duties, albeit with a leadership style that sometimes clashed with the needs and expectations of those he led. William Bligh’s life is a study in contrasts—his unparalleled navigational achievements and resilience in the face of adversity stand against the backdrop of his leadership controversies. His story offers invaluable lessons on the importance of adaptability, empathy, and the ability to lead under the most challenging conditions.

@thenetworkofconsultingprofessionals