“Ability is of little account without opportunity.“

– Napoleon Bonaparte

Could World War II have been avoided?

Perhaps…

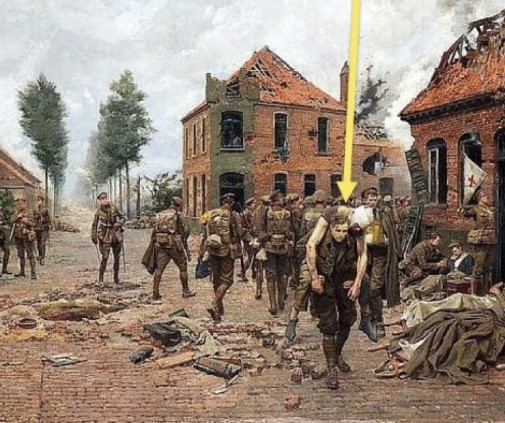

During World War I on September 28, 1918, a British soldier, Henry Tandey VC DCM MM allegedly spared Adolf Hitler’s life. Near the French village of Marcoing, he reportedly encountered a wounded German soldier and declined to shoot him. This soldier was believed to be Adolf Hitler. If he had shot Hitler perhaps World War II would have been avoided?

Was it true?

Well, no.

There were logistical inconsistencies in the story, such as the unlikely chance of Hitler, who was reportedly on leave in Germany, being in the same area as Tandey at the time. Also interestingly, the date was same one on which Tandey won his VC. This could not be a co-incidence. In 1938, British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain was visiting Hitler for talks that led to the Munich Agreement, and whilst there noticed a painting of a 1914 World War I soldier purported to be Tandey, carrying a wounded man. Apparently, he asked about it, and Hitler replied:

“That man came so near to killing me that I thought I should never see Germany again; Providence saved me from such devilishly accurate fire as those English boys were aiming at us”

The Nazis were masters of propaganda and Hitler most likely concocted this story to portray himself has a great leader who was saved to lead the German people. It was his destiny. Additionally, the likelihood of Hitler recognising Tandey 20 years after ‘the event’ from a painting is questionable, given the circumstances of war, where recognising people would be challenging.

Are there any lessons for us as managers in this story?

From a personal point of view, chance or luck does play a part in our careers. By chance I saw an advertisement in a newspaper for a postgraduate degree in logistics. Working in the construction materials industry, I realised that transport was critical in the industry. I subsequently completed the study. This led to a career change into a different industry and some casual lecturing at university.

However, more importantly preparation is critical. Having studied I was able to change jobs more readily. As Jack Gibson the legendary Rugby League coach said:

“Luck is where preparation meets opportunity”

Other lessons include the importance of critically evaluating information and not accepting stories at face value. As managers we should encourage a culture where claims and decisions are based on evidence and rational analysis rather than myths.

Also, Hitler’s possible use of the story to enhance his image demonstrates how myths can be constructed around leaders. As managers, we should be cautious about myth-making in leadership, focusing instead on authentic, transparent, and ethical leadership practices.

There is no strong historical evidence to support it. The historical consensus leans towards considering it a dubious account, likely embellished or entirely fabricated by Hitler for propaganda purposes.

Can you think of any other lessons from this myth?

@thenetworkofconsultingprofessionals