“Extinction is the rule. Survival is the exception” – Carl Sagan – US Astronomer and Scientist

The phrase “dead as a Dodo” is not just a metaphor, but an epitaph to the extinction of the Dodo. The Dodo was a bird that inhabited Mauritius, an island in the Indian Ocean and its extinction can provide invaluable lessons for today’s managers.

The Dodo’s Tale: A Cautionary Account

The Dodo, a flightless bird closely related to the pigeon was discovered by Dutch sailors in 1598. It had a bulky body, stumpy wings, and a distinctive beak. It lived in a habitat that was, until then, untouched by humans or any significant predators, which contributed to its fearlessness towards humans. This trait would contribute to its downfall.

The Dodo’s lack of fear was not an anomaly in the natural world but rather a common trait among species that evolve in isolated ecosystems, free from natural predators. For example, when humans arrived on Kangaroo Island, just off the coast of South Australia the kangaroos were unafraid of humans and were easily killed by early explorer including Mathew Flinders and Baudin. With the rising of the ocean, the Aboriginals had left the island thousands of years previously. Furthermore, it has also been hypothesised that the megafauna in Australia (Australia is the only continent apart from Antarctica that does not have megafauna), unafraid of humans were killed when the Aboriginals arrived from the north. This naivety, while initially an evolutionary advantage in predator-free environments, became a critical vulnerability with the arrival of humans and other animals that accompanied them.

The Downfall of the Dodo

The extinction of the Dodo was a tragedy. It stemmed from the bird’s inability to adapt to the rapid changes brought about by human colonisation. The factors leading to its extinction included direct overhunting by sailors for food, habitat destruction due to settlement and agriculture, and the introduction of invasive species like rats, pigs, and monkeys. They preyed on Dodo eggs and competed for food resources. By 1662, less than a century after its discovery, the Dodo was seen for the last time.

What are the lessons for modern managers?

1. Sustainability as a Cornerstone

The Dodo’s extinction underscores the critical importance of sustainable practices. For today’s managers, this translates into a mandate to balance growth with ensuring that business operations do not deplete or destroy natural resources. Aside from the environmental concerns today’s managers need to ensure the business is sustainable. For example, training and empowering staff, increasing and maintaining productivity, successfully implementing new technologies etc. The Dodo teaches us that exploitation without consideration of sustainability both environmental and financial leads to loss in the long term.

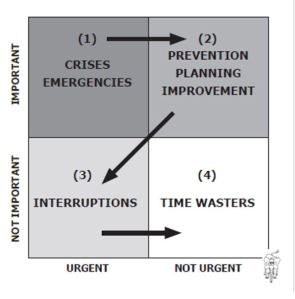

2. The Imperative of Adaptability

The Dodo’s inability to adapt to new threats underscores the importance of adaptability in the business world. In an era marked by rapid technological advancements and shifting market dynamics, companies must be agile, ready to pivot strategies, embrace innovation, and respond to emerging challenges and opportunities. Good managers foster a culture of continuous learning and flexibility, preparing their teams to navigate change effectively. The dodo’s fate is a stark reminder that those who cannot adapt are doomed to obsolescence.

3. Foresight and the Management of Unintended Consequences

The unforeseen impacts of introducing invasive species to Mauritius echo the modern-day need for managers to anticipate and mitigate the unintended consequences of their decisions. This requires a deep understanding of the complex interdependencies within systems, whether they be ecological, economic, or social and the foresight to identify potential ripple effects. This can involve conducting risk assessments, taking into consideration the broader implications of their strategies as well as developing robust contingency plans to safeguard against unforeseen outcomes.

Conclusion

The Dodo is not an isolated case; history is replete with species that have suffered similar fates due to their lack of fear of humans from the Great Auk in the North Atlantic, and the Tasmanian Tiger in Australia. The “dead as a Dodo” metaphor acts as a call to action for today’s managers. In an age where the pace of change is relentless, these lessons are not just optional; they are essential for ensuring businesses do not merely survive, but thrive responsibly.

As a manager, what do you think?

@thenetworkofconsultingprofessionals