“I am ready to try an airlift. I can’t guarantee it will work. I am sure that even at its best, people are going to be cold and people are going to be hungry. And if the people of Berlin won’t stand that, it will fail. And I don’t want to go into this unless I have your assurance that the people will be heavily in approval.”

Lucius D. Clay, June 1948

Military Governor of the United States Zone, Germany (1947 to 1949)

The Berlin Airlift. 75 years ago this month the Berlin Airlift ‘officially’ finished.

What was it?

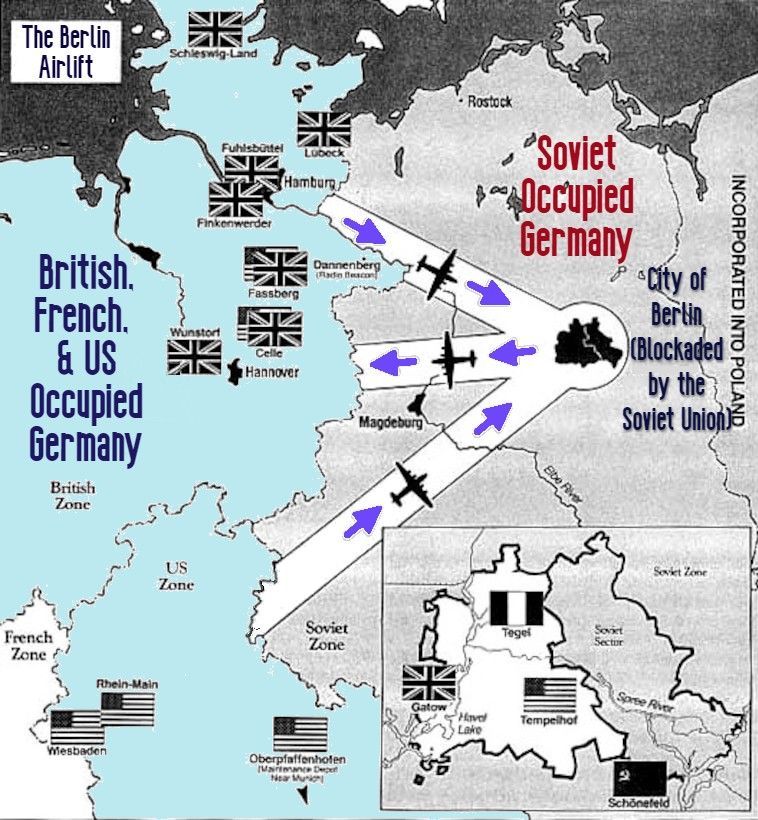

After World War II, Germany was divided into four zones, Soviet Russia, Britain, France and the USA. Berlin was also divided into four zones but lay within the Soviet Russian zone. On 24 June 1948, Soviet forces blockaded all road, rail and water routes into Berlin’s Allied-controlled areas. This stifled the vital flow of food, coal and other supplies. More than 2 million Berliners were relying on the aid, which included much-needed food, fuel and medicine and would otherwise starve and freeze. Two thirds of what was needed was coal.

However, the Russians could not block the Allied airspace. On 24 June 1948. The Allies established an airbridge and began an airlift that lasted officially until 12 May 1949 when the Soviet Union lifted the blockade. The airlift continued until September after the lifting of the blockade as the Allies wanted to make sure that it was not reintroduced.

Why did it occur?

The blockade was an attempt by Soviet Russia to gain control over the entire city by cutting off all land and water routes to West Berlin, which was then under the control of the Western Allies.

Logistics of the Berlin Airlift

The success of the airlift depended on meticulous planning and execution. The planes were scheduled to land and take off at precise intervals, ensuring a continuous flow of supplies. This required exceptional coordination among pilots, ground crews, and logistics teams. To maximise efficiency, the cargo planes followed specific flight paths and adhered to strict timetables. This was all before the use of computers, GPS tracking and scheduling which we have today.

The airlift involved transporting a wide range of supplies, including food, coal, medicine, and machinery. Each type of cargo required different handling and storage conditions, which added complexity to the logistics operation.

Berlin Airlift – Facts & Figures

- One aircraft landing per minute

- Over 200 million miles flown

- Each aircraft unloaded in 20-30 minutes

- 2000 tonnes of food required per day

- 400,000 tonnes of food, supplies and coal

- Over 200,000 kms flown

- 277,804 flights completed

- 93 lives lost

The airlift cost the United States $350 million; the UK £17 million and Western Germany 150 million Deutschmarks.

What are three lessons for business leaders in the example of the Berlin Airlift?

- Innovative Problem-Solving: Leaders had to think creatively and act decisively to overcome the blockade. This required innovative strategies, such as the airlift, which had never been attempted on such a scale.

- Resilience and Determination: Leaders demonstrated resilience and determination in the face of adversity. The operation continued for over a year, and the leaders remained committed to their mission despite the challenges.

- Precision and Coordination: The operation demonstrated the critical role of precision and coordination in logistics. Timely delivery and efficient turnaround were essential for the success of the airlift.

In conclusion, the Berlin Airlift was not only a remarkable logistical achievement but also a powerful example of international cooperation, innovative problem-solving, and leadership under pressure. It provided invaluable lessons in both logistics management and leadership that are still relevant today.

What do you think?

Note: 39 British, 31 American and 13 German civilians lost their lives in the Berlin Airlift. They are remembered on the Berlin Airlift monument at Tempelhof. The pilots came from the USA, Britain and France and also from Australia, Canada, South Africa and New Zealand.

@thenetworkofconsultingprofessionals