“Some people think football is a matter of life and death. I assure you, it’s much more serious than that”

Bill Shankly – Successful Coach of Liverpool United

In Australia, the late September and early October period is ‘grand final’ time for the two major football codes, Rugby League (NRL) and Australian Rules (AFL). Australian comedians and sports personalities ‘Rampaging’ Roy Slaven and HG Nelson call it ‘the festival of the boot’.

Politics, family, lifestyle issues, cost of living and food are forgotten about for a couple of weeks of dreams as fans ponder the outcomes.

This is a great opportunity to discuss sport as it relates to business…

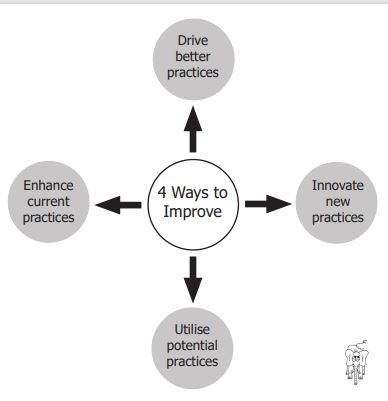

So, does sport have some lessons for managers?

What can we learn?

Here are three lessons to consider:

1. Recruit the right people, then develop and manage

One of the most important lessons that businesses can learn from sport is to recruit the right people (emphasis on the ‘right’) and not necessarily the ‘best’ people. For a team to work, there needs to be diversity but underpinned by shared values. You can teach people new skills, but you can’t always teach them how to behave. Once you have a good team player – make sure you keep hold of them. Just because someone is the ‘right’ person, doesn’t mean that they will not require guidance.

One Australian Rugby League team of recent times that stands out in this regard is the Melbourne Storm. Only established in 1998 in Melbourne in the heart of AFL country, the club won the Premiership in only its second year and went on to win many more Premierships. Through long term coach Craig Bellamy and his coaching team, the Storm have identified and developed players who were not identified or sort after by other clubs. Bellamy began coaching the Storm in 2003 and is still the head coach!

In our logistics business, we identified floor staff who had potential, with the right values, were ‘trainable’, have the work ethic and values. Many were casuals hired though labour hire agencies. They were made permanent staff, became supervisors and several became warehouse managers.

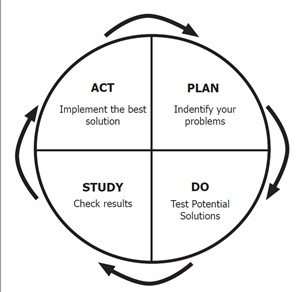

2. Being resilient and overcoming adversity

In sport, as in business, change is inevitable. But it is how you deal with the change that can be a make or break decision. For athletes being mentally resilient is as important, if not more, than an athlete’s physical ability. Being able to deal with adversity, hard training sessions and setbacks strengthens an athlete and further pushes them to be the best that they can be.

A great example of resilience is the winner of Australia’s first Winter Olympic Gold Medal, Stephen Bradbury in 2002. Bradbury won the Gold Medal when all the other competitors crashed. However, what few people realised, is that behind the win were years of hard work and serious injuries.

For us in business, mental resilience is also an important component for success, as pulling through the tough times and remaining positive in the face of adversity can create opportunities. In my former logistics business, in the space of three months we lost two of our largest customers. They represented 30% of our business. This looked like a disaster. However, we implemented a plan, knuckled down and within 12 months our revenue grew by over 50%.

3. Embrace Team Diversity

A very good example is the 1995 Rugby World Cup winner South Africa. President Nelson Mandela, in a move to unify a racially divided country, supported the traditionally white-dominated South African Springbok rugby team during the Rugby World Cup. Team captain Francois Pienaar, understanding the importance of this gesture, worked to bring his team together, focusing on shared goals rather than individual differences. Led by Mandela and Pienaar, they showcased the power of embracing diversity by beating the favourites, the New Zealand All Blacks.

Before I went into business for myself, I worked for a national transport business. The CEO was a larger-than-life character, well known and respected in the industry with a work ethic second to none. Within the business was a national operations manager who was highly skilled and driven, much like the CEO. He was seen by the CEO as ‘the type’ of manager the business needed. At the time my wife, an industrial psychologist was providing some professional services to the business and was asked to draw up the ‘essential’ characteristics for the perfect manager so they could be replicated throughout the business. The vision being ‘clones’ throughout the business nationally. After some discussions the idea was dropped.

Businesses need a mix of people to meet their full potential. Whilst I am not advocating diversity for diversity’s sake as is frequently the case today, it is critical to have a diverse pool of experience and talent in an organisation. ‘Group think’ is dangerous and often the best ideas and actions come from a diverse workforce.

Sport offers a wealth of lessons for managers, providing insights into leadership, teamwork and success. Recruiting and developing the right people, being resilient and embracing diversity are just three of the lessons for us in business to learn from sport.

Can you think of other lessons we can learn from sport?

In the meantime, if you are in Australia enjoy the ‘festival of the boot’ the finals of the two football codes.

@thenetworkofconsultingprofessionals